Climate change dates back to dawn of first farmers

Chopping down trees with flint axes, planting peas and shearing sheep — those all sound like the prosaic duties of the earliest farmers.

But those same Stone Age sodbusters were likely changing our planet's climate, researchers are now suggesting, long before the greenhouse gas emissions of the industrial era. And that means the "Anthropocene" era, the time of humans making a mark on the planet more striking than natural forces, extends not just to the beginning of the industrial era but to the dawn of agriculture.

How could that be? Mostly because early farmers weren't so good at what they did some 7,000 years ago, suggests environmental scientist Bill Ruddiman of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

"How early farmers cleared forests is very different than today. They used a lot more land, and they cleared a lot more forest per farmer," Ruddiman says. In an Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences analysis, Ruddiman finds that archaeology shows climate scientists have underestimated just how many trees early farmers needed to cut down to feed their families. Early farmers didn't plant prairies that needed plows or fertilize the same fields every year. They cut down forests fed by rainfall, moving on to the next one in slash-and-burn fashion every few years after a plot's fertility faded. "All that added up to a lot more forest clearance than climate scientists suspected thousands of years ago," Ruddiman says, with concurrent atmospheric upticks in two important greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide and methane, long before the first fossil-fuel fires.[1]

Greenhouse gasses retain heat, warming the atmosphere. Global warming is mostly the man-made kick to this natural effect provided by adding greenhouse gases to the air through burning fossil fuels.

For more than a decade, most climate scientists marked the starting point of the Anthropocene[2] era as 1850, the point at which these two greenhouse gases began their exponential increase in the atmosphere, up to levels today unseen for at least the past 650,000 years[3]. Those increases are responsible for much of the 1.4-degree Fahrenheit increase in global average atmospheric temperatures during the modern era, according to the American Meteorological Society[4].

Since 2003 however, Ruddiman has instead argued that the Anthropocene's effects had kicked off global warming much earlier, starting thousands of years ago (the previous period would be the "Holocene," which started 10,000 years ago or so). And more climate scientists are agreeing with him on that today.

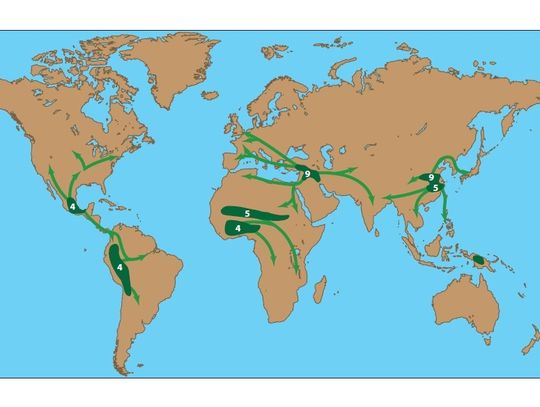

Agriculture's spread worldwide, with the numbers indicating thousands of years since its origin.(Photo: Earth Transformed by William Ruddiman. Copyright © 2013 by W. H. Freeman and Company. Used with permission.)

"The real question is whether people then really did have global impacts. I'm pretty sure they did," says atmospheric scientist James White[5] of the University of Colorado. "It's a fascinating idea."

The march of farming from the Fertile Crescent to Europe and the rest of Asia began 9,000 years ago, while rice irrigation spread from China starting about 6,500 years ago. Corn was farmed in Peru 5,000 years ago and spread throughout the New World thereafter, suggests a paper out Monday[6] from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. "Even before the Bronze Age, Europe was an agricultural region," Ruddiman notes in his analysis. All those rice paddies, barley fields, goats, cows, sheep and other livestock burped out more methane into the air. And clearing and burning all the trees to create those first farms, more than 1.5 acres a year per person thousands of years ago, according to archaeologist's estimates, also added more carbon dioxide to the air.[7] Essentially, farmers cleared 70% more land in China, India and Europe before the industrial era than past estimates had allowed, Ruddiman concludes.

The results would be greenhouse gas emissions that while not as large as today's would have had a significant warming impact on the climate over thousands of years, essentially providing a roughly 10% increase in atmospheric methane and carbon dioxide concentrations.

The clearest signal of this effect comes from the 1500s, when the arrival of Columbus led to widespread depopulation of the New World through diseases such as smallpox, a devastating loss to humanity documented in Charles Mann's 2006 book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. A series of studies, most recently an October report[8] in the journal Nature looking at ice-core records, tie drops in methane linked to the reforestation of a depopulated New World to cooling periods known as the "Little Ice Age" starting after 1560.

"It is not a big change compared to what we have done since, but there it is," says climate expert Richard Alley of Penn State, who was a co-author on the Nature study. While scientists cannot absolutely prove it, Alley says, "The evidence does seem to show that humans were having a big ecological impact early in the Holocene and before, with some record in the atmosphere."

Ruddiman has become tangled in debate with Columbia University's Wallace Broecker over whether the effects of this early warming would have been enough to forestall another Ice Age like the one that ended roughly 13,300 years ago. Broecker says he doesn't see enough evidence to agree that folks had any pre-industrial effects on the climate whatsoever, it is worth noting. But Alley says the Ice Age debate is a sideshow, beside the staggering suggestion that early farmers had some effect regardless.

"I think it is much more interesting, and instructive, to note that early humans had so much impact on the planet, as Bill (Ruddiman)'s work and much other research is showing," says Alley, author of Earth: The Operator's Manual. "In some ways, our impact per person has probably been dropping as we learned better ways to do things, although our population appears to have been growing faster than our impact per person dropped, so we're having more total impact across the planet."

Ruddiman is similarly hopeful that people can learn to have even less impact on the planet, and that investigations into prehistoric people can help explain more mysteries about past climate questions. "I think climate science and archaeology both have a lot more to say to each other," he says.

References

- ^ http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-earth-050212-123944?journalCode=earth& (www.annualreviews.org)

- ^ http://oceanworld.tamu.edu/resources/oceanography-book/anthropocene.htm (oceanworld.tamu.edu)

- ^ http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/science/indicators/ghg/ghg-concentrations.html (www.epa.gov)

- ^ http://www.ametsoc.org/policy/2012climatechange.html (www.ametsoc.org)

- ^ http://instaar.colorado.edu/people/themes/category/climate-indicators/ (instaar.colorado.edu)

- ^ http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2013/02/19/1219425110.abstract (www.pnas.org)

- ^ http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/71932/description/Climate_meddling_dates_back_8000_years (www.sciencenews.org)

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23038470 (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)