When to believe the hype

Brands are starting to use the ‘hype cycle’ as a shortcut for expressing where new technologies are in their lifecycle and basing business decisions on what they find. How can marketers use this framework to help develop new products and services?

If you believe the hype, driverless vehicles, embedded sensors, immersive interfaces and a host of new wearable technology will soon be changing the world as we know it.

But which of these new technologies will become an imminent marketable reality and which of them are destined for another decade of development? The ‘hype cycle’, a five stage development curve can help marketers distill what’s hot from just hype.

Marketers ask themselves questions like these every day because timing is everything. If a brand launches a product too early, consumers might not be ready for it, but, if the early launch is successful – such as with Nike’s FuelBand – they can be first to market.

Come in late, however, and although the brand can learn from others’ experience, it runs the risk of failing to penetrate an already saturated market.

Morrisons , for example, has only just launched an online delivery service , following belatedly in the footsteps of the other major supermarkets. As digital marketing director Amanda Metcalf says, this has “effectively forced people into our competitors’ hands” (see Q&A).[1][2][3]

Five stages of hype

As they seek help in navigating the product launch journey, many are using the ‘hype cycle’: a five-point framework first developed in 1995 by research company Gartner that tracks the evolution of emerging technologies.

This framework can assist marketers in deciding when to launch new products – and shows that being first to market does not necessarily guarantee success.

Put simply, the concept of the hype cycle suggests that the life cycle of all new technologies follows a similar, five-step pattern (see ‘Five stages of the hype cycle’).[4]

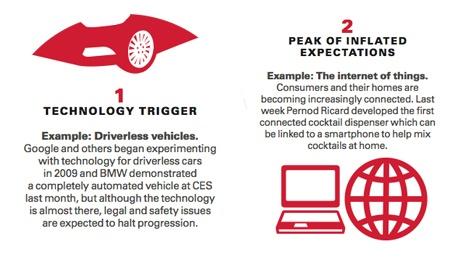

The first stage is the ‘technology trigger’, where an emerging technology is reported in the press after being exhibited at an event such as the Consumer Electronics Show (CES).

This leads to the ‘peak of inflated expectations’, whereby brands launch products. Plenty of success stories exist for this stage but there are also many failures, causing companies to park their innovations.

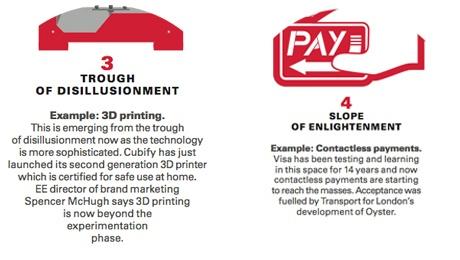

Next is the ‘trough of disillusionment’, where the new product or service does not live up to public expectations.

Once any problems have been ironed out on the ‘slope of enlightenment’, there follows an eventual move to maturity and mainstream adoption via the ‘plateau of productivity’.

“Often excitement about the possibility [of a new idea] hits reality and organisations realise it’s a darned sight harder to achieve what they want,” explains Gartner analyst Mark Raskino, who co-authored ‘Mastering the Hype Cycle’ with the originator of the model, vice-president and Gartner colleague Jackie Fenn.

“Sometimes it can take several years to solve the problems; very few things fail to come out of the ‘trough of disillusionment’ but when they do, they are often reshaped, rewrapped or remodelled.”

WAP banking, for example, was launched at the beginning of the millennium to enable consumers to access their bank account on a mobile phone, but it failed to meet expectations.

“It was totally premature,” says Raskino. “There was a lot of excitement about electronic commerce, which overlapped with the launch of the first Nokia phone with WAP-based access to data. People thought it was going to be huge, but it very quickly crashed and burned because the technology wasn’t very good and consumers weren’t ready.”

Waiting for the right moment

Although WAP banking has faded into insignificance, several years later in 2008/09 the first banking smartphone apps appeared.

“It’s essentially the same concept,” says Raskino, “but the banks went away and made it secure, made it perform, improved the consumer interface, integrated it with other systems and got people involved.”

Today the financial services sector is being shaken up again by the move towards contactless payments, but the technology is anything but new, says Visa Europe’s director of mobile, Mary Carol Harris, who began working in this space 14 years ago.

Visa spent several years concentrating on early-stage prototypes and consumer testing, but waited until 2007 before bringing the proposition to market, at which point it was confident of a clear call for the technology for secure use in low-value transactions.

Fast-forward to last year and Harris says: “Contactless is really beginning to take off as consumer awareness strengthens and the acceptance infrastructure falls into place.

“Contactless as a technology has been around for a long time and it was Transport for London [TfL] that really pioneered its use with Oyster. Its use of contactless is well beyond the ‘plateau of productivity’ now.”

She adds: “What we’ve done is modify that behaviour and change it into a new way to pay. The consumer behaviour piece was really key because most of the battle in getting consumers to adopt it for everyday use had already been won, particularly in London.”

Indeed, the number of contactless transactions increased fourfold in the UK last year, with £461.6m spent using Visa’s contactless cards. There are now 30 million cards in the UK, accounting for nearly a third of cards being used here. There are also 300,000 payment terminals, in addition to the 8,000 Oyster readers on London buses, and TfL will soon be extending the technology to the London Underground.

It is always a calculated risk to be the first to market in a new category. This makes consumer research very important

The transition might have been even quicker, says Harris, if Visa had focused initially on the bigger retailers rather than the smaller players. “But in technology terms, from the payment industry’s perspective it’s still been really fast,” she says.

Wearable technology

The popularity of wearable technology has also been growing steadily, with Nike leading the way in the fitness sector with the launch of the Nike+ FuelBand in 2012 (see Case Study).[5][6]

However, while Nike is widely accepted as the first major brand to launch a wristband activity tracker, it wasn’t the first company to do so. Jawbone launched Up in November 2011, while the FuelBand came afterwards in January 2012. FitBit has recently launched its next-generation wristband, FitBit force, in the US and is expected to bring it to the European market this spring.

Nike has auguably opened up the market for others and helped such technology go mainstream, allowing them to iterate more quickly and offer similar devices at a lower price (the ‘slope of enlightenment’).

“Our focus is product led rather than brand led,” says Gareth Jones, vice-president and general manager of Fitbit in the EMEA region.

He says the company, which made its name with activity tracking clips, is seeking to differentiate itself with the Fitbit Flex wristband by offering real-time syncing to many more devices.

Nike’s FuelBand was quickly emulated, with other brands able to make cheaper versions

“When we launched Flex at CES in 2012, we talked about a product [featuring] technology that was entirely believable, present and existent in the marketplace in various other products or forms.

“What we aimed to do was bring it into the health and wellness market… and we are confident we have more features for less expenditure,” says Jones.

Matt Hill, editor of gadget magazine T3, says: “Nike is the pioneer in this market, first with Nike+ and then FuelBand, which has paved the way for all these other brands. They have a lot of catching up to do but they will be able to move a lot quicker.”

He believes the rise of wearable tech such as FuelBand has triggered a convergence of mass-market brands such as Nike, which have moved into the tech space, and specialist health tech firms such as Polar, which thanks to Nike have been able to slide into the mainstream.

Customer insight

Use of the hype curve to determine when to enter a market should always be based on customer insight, according to Jonathan Earle, head of customer strategy and development at O2 .

“Whether you launch at the start, midway through or even at the end of a product cycle depends on customer insight, together with how confident you are that what you are launching is something customers want.

“The reason so many brands fail at the start is because they launch something too quickly and don’t think about how they are going to guide the customer through the journey.”

Often excitement about a new idea hits reality and organisations realise it’s a darned site harder to achieve

Customer insight plays a vital role at Sony, which was one of the first to launch a smart watch product and is now a leader in the category. It bases product launches on “tech advances, user feedback and market demand”, according to Catherine Cherry, marketing director for Sony Mobile, North-West Europe.

She says: “It is always a calculated risk to be first to market in a new category. This makes consumer research very important. Sony is keen to pioneer new technologies and markets, and although being first can be hard, it means we are able to respond and bring out improved products faster than our competitors.

“That said, we only release products when there are significant enough advancements to warrant a new release.”

The brand is now on its third generation of smart watch, having recently launched SmartWatch 2 with additional features including one-touch NFC pairing with smartphones and better visibility in sunlight.

It has also made advances in the fitness tracker space in a bid to rival Nike, having launched its SmartBand with Core technology last month.

Defying adversity

Knowing when to stick with a good idea even when facing obstacles is also key to achieving a successful product launch, says Gartner’s Raskino, who cites the contrasting ways in which Tesco[7] and the now defunct Safeway supermarket handled the development of their loyalty cards.

Both supermarkets committed a lot of money to their respective initiatives, but Safeway abandoned its scheme after about four years when the idea hit the ‘trough of disillusionment’.

Tesco, however, persevered with its Clubcard concept and began adapting the business based on the data obtained.

“Most analysts now say Clubcard is one of the things that has made Tesco great,” says Raskino. “The company didn’t give up on the idea when others did, which is a hard thing to do.”

Morrisons[8] , which acquired the flagging Safeway business in 2004, acknowledged recently that its lack of a data-driven loyalty scheme [9] was one of the reasons for its poor Christmas figures. It is set to start trialling a new programme in the next four to six weeks.

Morrisons was also very slow to launch its online offering[10] , coming to market more than a decade after Tesco. However, while the company lacks experience in this area, Morrisons digital marketing director Amanda Metcalf says coming to ecommerce late has enabled the business to learn from its competitors’ mistakes and tackle some of the trust issues that consumers have with online grocery shopping.

Sony is leader in the smart-watch sector and places great importance on consumer research when developing new technologies

“I wouldn’t say we’re happy to be going to market so late,” she admits. “Obviously, we would have loved to get there sooner, but we’re making up for lost time now by going to market with a transparent service that addresses some key consumer concerns.”

Evidence shows that shoppers are worried about freshness when ordering groceries online, so Morrisons guarantees shelf life on all fresh products and carries out doorstep checks to ensure the customer is satisfied before they accept their goods. If the customer is unhappy with an item for any reason, they receive an immediate refund and a voucher for the same amount off their next order.

Despite the insight that Morrisons has gained by waiting, the delay to market means its in-store customers have had to rely on other supermarkets for online groceries, which means it still has a job to do to penetrate what is becoming a mature market (see Q&A).[11] The task has become even harder after online operations director George Dymond resigned after just a few weeks[12] in the role.

There are no fixed rules for when different types of business should take the plunge with a product launch, and the use of the hype cycle is not an exact science. However, it can be a useful framework to help brands plot the life cycle of a new technology and, in turn, guide their business decisions on the best time to launch new products and services.

Five stages of the hype cycle

The cycle begins with a ‘technology trigger’ – a new technology that causes a buzz after early proof-of-concept stories prompt media interest. However, often no usable products exist and commercial viability is unproven. This leads to the ‘peak of inflated expectations’.

Early publicity produces some success stories but these are often coupled with failures. Some companies persevere but many do not, causing the technology to enter the ‘trough of disillusionment’ as interest wanes when experiments and implementations fail to deliver. Those that persist work to solve the early problems and improve the product, which can take several Products that emerge from the trough are often reshaped, setting them on the ‘slope of enlightenment’.

More examples emerge highlighting the benefits of the new technology and it becomes more widely understood. As the market matures, second- and third-generation products appear and more businesses fund trials. Conservative companies remain cautious, however.

Eventually, the concept reaches the ‘plateau of productivity’ and mainstream adoption begins to take off.

Source: Gartner

Hot or hype, how to judge when to dive in

Do not follow the crowd

The main problem with the ‘peak of inflated expectations’ is that many companies feel they must take action because their competitors have, although their technology may not be ready.

“Don’t get sucked in and do something just because it’s ‘hot’,” says Gartner analyst Mark Raskino. “‘Me too’ companies tend to be less committed so when things fall into the ‘trough of disillusionment’, they run away and end up wasting their time.

“It’s actually the one or two companies that have led the way that might grind through and come out the other side.”

Ensure customers are ready

“Sometimes even marketers who say they are customer driven aren’t actually listening to what customers are saying,” says Raskino. “When something is in the ‘trough of disillusionment’, marketers need to ask themselves if it is fundamentally a strong idea. If it is, they should not give up on it.

“Being flighty and going back to the peak looking for the next big thing will not win prizes. As the ‘slope of enlightenment’ approaches, companies need to consider how substantial this technology is likely to be for their industry.”

Build in deep competency

Companies that work through the ‘trough of disillusionment’ to eventual success have fully embedded all of their insight into the business. They know what works and what does not and have people and processes in place, says Raskino.

“If you let everyone else skin their knees and look stupid on the ‘slope of enlightenment’ and just buy your way in, it can be difficult to succeed because you’re not just buying a technology or a product, you’re buying a thinking pattern, an organisation structure and a group of specialists. These things are not always easy to absorb.”

Case study: Nike FuelBand

“It’s been great to watch the market evolve and understand what is truly valuable for athletes,” says Ricky Engelberg, Nike Digital Sport senior director for innovation, who was instrumental in developing Nike Fuel and the Nike+ FuelBand.

Being a part of athletes’ lives has enabled the sports giant to operate on instinct when launching new products, he adds.

“We had tremendous success with Nike+ Running when we launched in 2007, but felt it wasn’t enough to only motivate runners. We knew there was an opportunity to connect every athlete with this common language, whether tennis player, basketball player or runner.”

However, sometimes ideas emerge ahead of what technology will allow. “In 2007, the technology existed for us to deliver [the app] for runners, but it didn’t exist to connect every athlete. As time went by, the hope of connecting all athletes became more realistic and the technology and our dreams matched up in 2012.”

The brand gathered market knowledge from its existing product portfolio, which it used to improve the Nike Fuel offering. As a result, the Nike+ FuelBand has no proprietary cables that could become lost, it is made of a material designed for comfort and it has undergone rigorous testing to enable athletes to wear it for long periods.

“These new categories are a natural extension of what Nike has always done,” says Engelbert. “Now, it just happens that some of these things are digitally enabled.”

Q&A

Amanda Metcalf

Digital marketing director

Morrisons

Marketing Week (MW): What has been the main disadvantage of launching Morrisons’ online grocery service last month - later than all its competitors?

Amanda Metcalf (AM): We effectively forced people into our competitors’ hands in the online space, so we will have to work really hard to get them back. As we’re late to market, we also don’t have full geographical coverage yet. We hope to be serving half the UK population by the end of 2014, but there are people desperate to take advantage of our online offer whom we will not be able to get to this year, which is frustrating.

MW: Are you starting to see some of the customers who defected return?

AM: We are beginning to pull Morrisons customers back. Our evidence shows that the early adopters of the service are our loyal in-store shoppers who were shopping with our competitors online.

MW: What has the partnership with Ocado enabled you to do?

AM: It has sped up the process enormously. We looked at setting up the service organically but it would probably have taken us three to four years just to get to a starting point. But with Ocado, within nine months we’ve gone from nothing to a semi-live business.

MW: How do you foresee the online grocery market developing?

AM: All the signs are that this is about to become a very mature part of the market. When we look at the postcodes we deliver to and the different demographics, a lot of families on a budget are using online shopping to manage their spending. They can see a running total, they can add and take away from the basket to stay within budget and they don’t get tempted by offers in-store.

References

- ^ Morrisons (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ launched an online delivery service (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ (see Q&A). (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ (see ‘Five stages of the hype cycle’). (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ Nike (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ (see Case Study). (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ Tesco (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ Morrisons (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ lack of a data-driven loyalty scheme (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ launch its online offering (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ (see Q&A). (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ George Dymond resigned after just a few weeks (www.marketingweek.co.uk)