Launching in Russia

Russia’s middle class is undergoing phenomenal growth and is predicted to represent 86 per cent of the population by 2020 with a spending power of $1.3trn. Savvy brands are entering the market now to target this next big opportunity.

Russia has been, if not in the hearts, then in the sights of Western brands over the past two decades, as they have sought to gain a foothold in the world’s biggest country while negotiating the political, economic and cultural difficulties posed by the evolving superpower.

In the past year a number of major brands have made their move, with Apple[1], Asos[2] and Debenhams launching in the country, as well as super-franchise Peppa Pig. Meanwhile, Amazon has reportedly filed documents to open its first office in Russia after online auction site eBay opened an office in Moscow last year.

Although political relations between the West and East remain tetchy at best, the business case for entering Russia appears increasingly attractive. Earlier this year, market research firm Nielsen noted that “stable gross domestic product growth, declining inflation and a record-low unemployment rate are pointing to positive consumer purchasing power in Russia”.

According to the Brookings Institution, the Russian middle class will grow by 16 per cent between now and 2020, at which point it will represent 86 per cent of the population and amount to $1.3trn (£852bn) in spending, up 40 per cent on 2010. Russia, along with other BRIC countries Brazil, India and China, could contribute to a combined economy larger than the world’s richest countries by 2050, according to Goldman Sachs.

While some brands have stayed away, put off by the challenges of this complex market, others are targeting Russia as their next big growth opportunity, encouraged by the rise of the middle class and the government’s efforts to project a more presentable face to the world through events like the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics and the FIFA World Cup in 2018.

Marks & Spencer[3], which is growing quickly in Russia and now has 38 stores there, benefits from the country’s lack of home-grown fashion chains and a rising demand for its affordable retail offer, explains international director Jan Heere. He says that the company’s biggest competitors are other western brands such as River Island, Topshop and H&M, rather than Russian-owned outlets that are more likely to specialise in luxury goods.

There’s a strong appetite for western brands in Russia. There are local players but they don’t have the maturity of the west’s

“There’s a strong appetite for western brands [in Russia],” he says. “There are local players but they don’t have the maturity that western brands bring in terms of product development and branding.”

Heere, who was previously general manager for Russia at Zara owner Inditex, says that M&S has made subtle changes to cater for the Russian market, such as pushing its higher-end fashion lines to the fore and promoting materials like cashmere and wool, which are popular in Russian fashion. Overall, though, the brand presents itself in the same price and value terms as it does in its home market, tapping into the demand for mid- market shopping in Russia.

M&S’s success reflects a shift in Russian consumer behaviour as the growing middle class moves the country away from the ostentatious ‘bling’ culture of the elites who secured the country’s top jobs following the fall of communism. Ian Wood, global strategy director at Landor, a marketing agency that works with brands in Russia, suggests that while some of the more decadent aspects of this culture remain, consumers are now taking a more open and value- driven approach to brands and spending.

“I wouldn’t say that [Russian consumers] are the same as us but they are beginning to share those characteristics that are more sophisticated and discerning,” he notes. “It’s much more about judging quality and price. The bling thing hasn’t gone away but it’s almost like Russia has gone through a teenage period and is growing up fast.”

M&S is aiming to grow its international business, which covers 51 countries, in order to offset its struggles in the UK and Russia is an important element in that strategy. The retailer plans to launch an ecommerce platform in Russia later this year to further build its presence.

The company does not provide figures for individual markets but Heere says the retailer is enjoying double-digit growth in Russia and that “it is one of the countries where we want to grow at a good pace in the coming years”.

M&S (above) and Peppa Pig (below) are among the British brands courting Russia’s middle class

Although he concedes that there are obstacles to doing business in Russia, he believes brands can flourish if they work with established partners and understand local conditions. M&S runs a franchise model in Russia through Fiba Group, a conglomerate that also manages the retailer’s presence in Turkey and Ukraine.

“The franchise team knows the market and that gives us an advantage over competitors that might struggle to find space, to clear customs or to understand the changes in legislation,” adds Heere. “There are challenges so you have to research your business to cut through the bureaucracy.”

Debenhams also credits local partners for helping it to establish a presence. The retailer opened its first store in Moscow last September through Debruss, a franchise company set up in partnership with Russian business interests. Debenhams is also targeting major growth outside the UK and aims to double the size of its international business in the next five years. This includes eight more Russian stores (see Q&A[4]).

“Russia should be one of the key markets for any retailer looking for big [international] expansion,” claims John Scott, head of international business development at Debenhams.

“Many retailers have gone to the Middle East because it’s probably one of the easiest markets to start with, but after that Russia offers the biggest opportunity for growth from a European perspective.”

Scott confirms that Debenhams will initially focus its attention on Moscow, which is Russia’s most populous city with 12 million people. The second largest centre, St Petersburg, has nearly 5 million, followed by a number of cities of a million people or less. This disparity means that many brands pursue a separate Moscow strategy before looking at the rest of Russia. “You’ve got to make sure that the economics of your model work in the other cities,” says Scott. “We would look at it if the right opportunities came up.”

Debenhams ran a major PR campaign to raise brand awareness during its store launch. This included an event at the British Embassy in Moscow that was attended by famous fashion designers and the Russian press. The retailer also developed its social media presence by running a Facebook competition that offered one person the chance to meet the designers and attend the party. Scott says that Debenhams has used its British heritage in order to appeal to Russian consumers.

“There’s definitely a love of all things British and we played on that in our marketing,” he explains.

This affection for British brands extends to other western companies that have succeeded in injecting something new into Russian life. Frozen foods company Iglo, which owns Birds Eye in the UK, has grown quickly in Russia as consumers have been tempted by new products such as fish fingers and ready meals (see Case Study[5]).

European managing director Achim Eichenlaub explains the company has worked hard to gain acceptance for its products in a country where frozen food was less processed. “Russia is very much a natural market – they used to just eat fish, not fish fingers, coated fish or what we call value-added fish,” he says. “So we had to create that value-added market, develop ready meal solutions and find the right recipes to fit the market.”

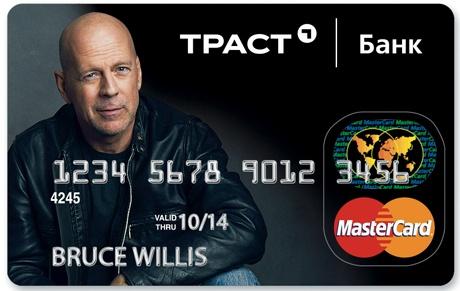

Private Russian bank Trust Bank has mixed its knowledge of the local market with marketing practices of global brands to increase its customer base

However, despite the success stories, it would be wrong to assume that all foreign brands can thrive in the country. This year Apple launched its first online store in Russia but the company is struggling to replicate its global success in the country after falling out with OAO Mobile TeleSystems (MTS), Russia’s largest mobile phone operator.

At the end of last year, MTS stopped selling the latest iPhone in its shops over concerns that Apple was charging excessive fees to operators. This month Bloomberg reported that these moves had coincided with a fall in Apple’s share of the Russian smartphone market in the first quarter of the year to 8.3 per cent. Meanwhile, sales of the Windows Phone, which MTS is promoting in place of the iPhone, rose to almost match this, according to figures from research firm IDC.

Wood at Landor also points out that in addition to contending with different business practices in Russia, many western brands will still face competition from home-grown companies. Landor is working on projects in Russia aimed at developing ‘Silicon Valley-type’ areas and domestic technology brands – partly in response to the influx of western companies.

“[Russian president Vladimir] Putin has challenged the country to start creating Russian brands, infrastructure and entrepreneurialism,” he says. “The wealth of the country has historically been built on natural resources and the projections for that are declining, so as a nation they need to create value through other areas.”

Although the Russian state still has big stakes in national industries, innovation is coming from the many private Russian businesses that have achieved a degree of freedom from state interference.

Private Russian bank Trust Bank, for example, has grown its customer base by combining its knowledge of the local market with marketing practices commonly used by major brands around the world. In 2010, it signed Hollywood star Bruce Willis to front all its marketing activity and continues to use him in a series of expensive activations, including a $6.5m TV campaign.

Putin has challenged the country to start creating Russian brands, infrastructure and entrepreneurialism

Working with Russian marketing agency Paradigma, the bank has tried to use the partnership in innovative ways, such as by encouraging customers to have their photos taken next to cardboard cut-outs of Willis in its 260 branches and upload them to social media. Trust Bank reports the partnership has helped it soar up the bank brand awareness rankings in Russia, rising from 20th place in 2010 to third in March 2013, according to research firm Market Up.

Vice-president of communications Dmitry Chukseyev says that celebrity marketing is still a relatively “nascent concept” among Russian brands but that the bank decided to go for this approach in order to grab consumers’ attention and attract global interest. He suggests that in contrast to Russia’s many state-owned banks, Trust Bank’s private ownership granted it the flexibility to take a risk on an expensive campaign that it felt would reap strong returns.

“We immediately hit 90 per cent of the Russian population because Bruce Willis’s films are all over the television,” he says. “After our first year, we were such a hit with Bruce – we were quoted by television presenters, we were joked about in a good sense on the top TV show in Russia and our brand recognition really went up.”

The proliferation of shared media content is also exposing Russia to new entertainment brands and franchises. Earlier this year, distributor Entertainment One launched British children’s television series Peppa Pig in Russia in order to build on the popularity of the franchise in other countries such as Australia, Spain and Italy. As part of the launch it is rolling out Peppa Pig merchandise, such as toys and stationery.

Head of global licensing Andrew Carley says that while the Russian market presents huge opportunities for the Peppa Pig brand, the company is conscious to follow the same roll-out process it would for any nation in order to ensure it carefully manages its growth across the huge and varied territory.

The logistics of trading across Russia, as well as concerns over excessive bureaucracy or corruption are challenges that all brands face in the country, although the government is working hard to improve Russia’s reputation for business around the world. Last August, for example, Russia joined the World Trade Organisation after 18 years of negotiations that had seen it become the last major global economy to remain outside of the international trading body.

The membership means Russia will have to obey a series of trading standards that include lowering import duties and granting greater access to European companies. The country is also reaching out to foreign brands through its hosting of next year’s Winter Olympics and the World Cup in 2018.

Buoyed by Russia’s economic growth and social and cultural developments, brands that have left the market are beginning to return. Last year, Burton’s Biscuit relaunched Wagon Wheels there after the brand was pulled from Russian shelves when the rouble collapsed and the economy was foundering in the late 1990s.

Chief commercial officer Steve Newiss says he is “delighted” with the sales since the relaunch but admits the company is playing the long game in Russia. The relaunch was focused on Moscow and the company is taking a city-by-city approach, which now also includes a roll-out in St Petersburg.

“Keeping it simple and focused helps us deal with the logistics issue,” says Newiss. “Given that this is working, there is a lot of temptation to think ‘shall we launch new products or take other brands over there?’ But while the model is working, I’m loath to complicate it.”

References

- ^ Apple (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ Asos (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ Marks & Spencer (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ see Q&A (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ see Case Study (www.marketingweek.co.uk)