How to stop your brand becoming a commodity

With the supermarkets all undercutting each other on price, what can marketers do to make sure they can still command a premium for their brands?

At the weekend (3/5/14), Tesco announced the roll out of 300 ‘pound zones’, areas in its shops that will sell branded goods for 50p and up. Last week, Morrisons became the latest ‘big four’ supermarket to launch a round of price cuts, cutting the cost of 1,700 products by 17 per cent. Meanwhile, The Co-operative Food has earmarked £100m for its pricing strategy and kicked off its ‘Fair and Square’ campaign.

Suppliers are likely to fund retailers’ price promotions and negotiations may be intense with a manufacturer trying to avoid discounting that can turn branded goods into commodities.

Meanwhile, in sectors such as insurance, having a well-known name may help a brand charge a premium but comparison websites encourage consumers to focus more on price than overall value. Some brands are charging the right price for their goods, while others could make better margins, according to a study by research firm BDRC Continental.

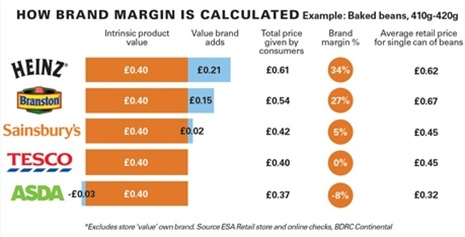

To help measure the effect ‘brand’ can have on the price a company can charge for a product, BDRC has developed a new Brand Margin metric. It has used it to examine several sectors, showing the results exclusively to Marketing Week (see below[1]).

The research shows, for example, that the price and brand value for baked beans are very aligned. The intrinsic value of a 410–420g tin of beans is 40p, but the value of the Heinz brand means people will pay an extra 21p for it, making the total 61p with a brand margin of 34 per cent. This compares to an average retail price of 62p, suggesting that Heinz is charging the right amount for its product.

Below are four ways to help marketers prevent their brand becoming a commodity.

1. Create an emotional connection

Heinz chief marketing officer Giles Jepson says that a variety of attributes will contribute to the price charged for a product.

“Value for money is multi-faceted; it is not just about price. In any consumer market there are different product offerings that connect differently with consumers, with different histories and reputations, experience and product attributes,” he says.

“Our communications have enabled an emotional connection that means consumers are able to make choices that go beyond just price.”

Apple tops the smartphone category with consumers adding 38 per cent to the intrinsic product value for an iPhone, but the research reveals brands in less fashionable and trend-led sectors can also command a premium.

The AA performs strongly in car insurance and breakdown cover, both of which are commodity categories where price is dominant.

It has a brand margin of 12 per cent in car insurance – three times that of any other company in the sector. Aviva and Halifax have a brand margin of 4 per cent, while Churchill and Direct Line have a 2 and 1 per cent brand margin respectively.

Those who do most of the shopping are going to have a greater affinity with the brands they buy because they understand the pricing on the shelf

Kwik Fit, Esure and Acorn Insurance have a negative brand margin of between -1 and -5 per cent, which means they need to do more to convince consumers of their brand value.

AA marketing director Michael Cutbill believes having a strong, recognisable and trusted brand allows the AA to command a premium.

“If you don’t have brand strength, then you will be knocked out by the next company that comes along and undercuts you, so brand strength is critical for stability,” he says.

“In the insurance market there are lots of example of brands that have done well for a short period based on a price strategy but they disappear quickly. We are a premium brand and we set out to have premium prices. Therefore we don’t say we’re the cheapest but we do say we offer the best service and we spend a lot of time substantiating that and making it a reality.”

James Myring, director of BDRC Continental, suggests the research indicates that the AA could charge more for its services because of the strength of the brand.

But Cutbill says: “Although it’s great to see that we have a 12 per cent brand premium, the truth is that price comparison websites make the whole motor insurance market incredibly competitive and as a result our prices are kept in check by the rest of the sector. We have to be reasonably competitive or we just won’t be seen.”

Women are the main shoppers of Mizkan products, which owns Sarson’s

2. Consider premiumisation

Audi has explored how its brand can influence the price of its luxury saloon car, specifically among highly affluent audiences.

It selected households using the Sky AdSmart platform, and was keen to evaluate the value this level of targeting adds to its campaigns.

Using the Brand Margin metric, respondents were asked to imagine that a new luxury saloon car was being launched in the UK at a price of £25,000. They were questioned about how much the addition of different car brands would add to the value of the vehicle. Among an untargeted ABC1 audience, respondents added £5,163 for the Audi brand, giving it a brand margin of 17 per cent.

Meanwhile, the targeted affluent audience added 19 per cent to the intrinsic value, putting an extra £5,898 on the value of the vehicle. Those exposed to the Audi ad via the Sky AdSmart platform added an extra £6,245 for the Audi brand, 20 per cent more than the unbranded vehicle.

BSkyB also claims that scores for exclusivity and innovation were also higher for the more affluent group, suggesting that there is potential for the brand to charge a premium for a new vehicle.

3. Create new pricing structures

Upmarket food brands such as Marks & Spencer and Waitrose had to adapt their pricing structures during the recession, with the latter launching Essential Waitrose and lauding it as a ‘billion pound brand’ this March.

Nathan Ansell, head of brand and marketing for Marks & Spencer food, Plan A and M&S Energy, says the way customers view the brand is one of the best and most challenging things about working for the retailer.

He says: “Customers expect M&S to be better than the branded alternative in most categories. They expect us to have a better product, a bigger range, more interesting flavours and superior quality.”

But it is this reputation that also enables it to command a premium price (see Q&A below[2]).

The retailer’s Make Today Delicious campaign positions M&S as a brand that can make “every day special” and is part of its effort to become more relevant for more occasions. Ansell says it has resulted in some of its relevance metrics increasing by 20 and 25 per cent.

M&S does well to command a premium for its food products, and does better than other retailers’ own-label brands, which tend to have a brand margin of close to 0 per cent in most sectors, according to BDRC’s research.

M&S has a brand margin of 24 per cent for smoothie products, scoring almost as highly as the category leader Innocent, which has 26 per cent. Both beat Tropicana (22 per cent ), Naked (20 per cent) and Dr Smoothie (17 per cent).

“This shows the power of the M&S brand in food and beverages,” says Myring. “Because of its reputation for quality it can command a high price premium. Our research suggests it could sell its products outside M&S stores and people would still buy them.”

4. Make the first move

As the first mainstream dedicated smoothie brand, Innocent also commands a premium. When the brand was launched it had no budget for advertising, according to group marketing director Franz Bruckner. He explains that choosing the right name was imperative as it was the principal way it communicated its brand promise.

“The name ‘Innocent’ is linked to our purpose: to make natural, delicious food and drink that help people live well and die old,” he says.

Marketing now represents “nothing less than our entire business” he adds, so everything the brand does, from the way it drives its vans and answers the phone to its advertising, are used to strengthen its overall brand position, enabling it to command a premium price in consumers’ eyes.

Consumers undervalue Ecover products yet the business has grown faster than mainstream competitors

Meanwhile, for environmentally-friendly laundry brand Ecover, which was one of the first brands to focus on eco-credentials, consumers undervalue the brand. Consumers value it at £4.50 when the average price is £8.50.

Myring argues this could be because of its environmental credentials, which gives it niche rather than mass market appeal. But this unique selling point and the fact that environment and sustainability have moved up consumers’ agendas has also enabled the business to grow quicker than mainstream competitors says Tim Smith, general manager of Ecover and sister brand Method.

“Data from the back end of last year shows that Ecover and Method were the fastest growing brands in the cleaning market during the recession,” he claims.

“We can place a premium on our products because of the way they are made and the ingredients we use. It’s similar to the issue around food provenance. Consumers understand that if they pay 99p for a frozen ready meal, they might have to think about the quality of the ingredients.

“That’s not to say that every consumer is willing to pay more but there is a market for consumers who are conscious about how a product is made and what is in it and are therefore choosing brands that have a close affinity to their own values.”

Price will always be a much debated issue for all businesses, but across the board it tends to be the strong, reliable brands that consumers have a strong affinity with which can command the highest premium in any given category.

How Premier Foods priced rice pudding

Before launching Ambrosia twin pots, Premier Foods did a series of tests to determine what price point it should launch at.

“Consumers make a very quick decision when they are in store so the price has got to feel right for the brand and the product,” says Claire Harrison-Church, category business director – sweet at Premier Foods.

“For any new product we will do quantitative research on purchase intent. We tell consumers about the product, what the content is, what the attributes are and we show them the packaging. We put in a range of pricing scenarios and then work back from that to determine what people are willing to pay.”

She says setting up pricing is very much a commercial decision, but that the brand teams work collaboratively on things like price elasticity, how the brand is positioned in the marketplace versus other brands and what the average category price is.

“We take all that into account when considering a price or price change on our brands and particularly when bringing new product development into the equation,” adds Harrison-Church.

Marketing then plays a critical role in setting up new products and building brand loyalty.

“Marketing has a huge impact on how consumers value our products because we’re investing in brands and brands help consumers make quick decisions about which products to buy. It has a massive impact on how people think and feel about those brands and therefore how they value them.”

Women would pay more than men

Women consistently value branded products higher than men, according to research by BDRC Continental.

Women give toothpaste an average brand margin of 26 per cent, for example, while men add 20 per cent to the to the intrinsic product value, and women give washing powder a 12 per cent brand margin while men add just 5 per cent to the basic price for branded goods.

Likewise, women give smoothies an average brand margin of 29 per cent compared to men who add 19 per cent, which shocks Nathan Ansell, Marks & Spencer’s head of brand and marketing for food, Plan A and M&S Energy.

“I’m surprised by this finding as most of our research shows that men are less price sensitive than women, largely because women do more of the shopping than men on the whole.”

When looking at various demographic data the disparity between how men and women value branded goods is one of the consistent trends, says James Myring, director of BDRC Continental. Differences in social grade and age didn’t have an impact on what people would pay for products, for example.

Even for more male-orientated or gender neutral products, women consistently give a higher brand margin than men. Within lager, for example, women add an average of 28 per cent for a branded product compared to men who add 19 per cent to the intrinsic value.

Similarly, women give airlines a 21 per cent brand margin, while men add 15 per cent, and for hotels women add 30 per cent to the intrinsic value, compared to men who add 19 per cent.

“I think the most convincing theory for this is that women control the majority of consumer expenditure, or at least partially influence it, and consequently they are the chief target for a lot of brand advertising,” says Myring.

Lorna Kimberley, head of marketing at Mizkan Europe, which owns Sarson’s vinegar and the Haywards and Branston pickle brands, has a similar view.

“Those that do the majority of the shopping are going to have a far greater affinity with the brands they buy because they understand the pricing on the shelf and the value. If women are valuing brands higher it could be that men are underestimating their value.”

While Mizkan’s main shoppers tends to be women aged over 45, the group is currently trying to target a younger male audience with the Haywards brand through its sponsorship of the Oddballs column in the Metro newspaper and upcoming sampling activity.

“Having a strong brand name instils trust in consumers and it’s that affinity with the British public which ultimately drives sales.”

Q&A

Nathan Ansell

Head of brand and marketing for food, Plan A and M&S Energy

Marks & Spencer

Marketing Week (MW): How do you decide where to position your products in terms of price?

Nathan Ansell (NA): We’re quite democratic. We have a team in the commercial division of the food group that is responsible for pricing and promotions but we’ll come together as a management team and collectively review our policy on pricing so it is definitely not exclusively a marketing decision, it’s a team decision.

We make calls about where we want to go with our policies on a fairly regular basis and try to be as competitive as possible but at the same time we are not a value retailer.

MW: What impact has introducing branded goods had on how you price M&S products?

NA: It has had some impact but I would say the launch of the Simply M&S range has been more transformational. Having hundreds of items in store that are price-checked versus competitors and come with a quality and price promise – that has probably made a bigger impact because it is a consistent brand that customers are seeing across the whole store rather than something they only see on branded goods. We only stock about 400 branded items, which is not that many.

MW: Do you always try to offer an M&S version to the branded alternative?

NA: There are many things we sell where we don’t have an M&S equivalent. For example we’ve just launched M&S baby food that we sell in the chiller cabinet but at the same time we decided to stock Pampers nappies because we want to demonstrate that we are a place to come to for a family shop.

We are never going to be big in nappies and it’s not an area we want to go into, so therefore we chose to stock Pampers nappies alongside our own brand baby food.

Price and the recession

Overvalued or undervalued?

The most frequently overvalued product over the past four years is a pint of semi skimmed milk. In 2010 people valued it 29 per cent higher than the average price which leapt to 76 per cent in 2013. Today people are still overvaluing milk but to a lesser degree at 26 per cent.

Conversely, a packet of 80 Huggies baby nappies is the most undervalued product. Consumer knocked 34 per cent off the value in 2010, which increased to 36 per cent in 2013 and again to 52 per cent in 2014.

The wrong price

Semi-skimmed milk has been the most overvalued product over the past four years with people presuming it costs an average of 44 per cent more, while Huggies nappies are the most undervalued. But consumers also are also way out when it comes to pricing a copy of the Daily Mail, as they added an average of 19 per cent to the cover price between 2010-2014.

At the other end of the scale Meanwhile consumers undervalue a standard ticket to Blackpool Pleasure Beach for one adult by an average of 38 per cent.

Everyday versus luxury

Consumers tend to undervalue luxury and special purchase products more than everyday items. An adult ticket to Blackpool Pleasure Beach is undervalued by an average of 38 per cent, while a new Ford Focus 1.8 Zetec car comes in 20 per cent under value.

For everyday items like a 750g bag of granulated sugar (-8 per cent) and a Kingsmill white sliced bread (-9 per cent) the difference is much less. But like milk consumers also overvalue half a dozen free range eggs adding an average of 7 per cent to the actual cost on average over the past four years.

Source: fast.MAP

Methodology

BDRC calculates brand margin using a ‘wisdom of crowds’ methodology - where people are asked ‘how much would someone pay for this’ and is based on the views of 1,000 consumers who were given an intrinsic value for a product and then asked what they would pay for a branded version. It takes into account solely customers’ perceptions of the prices of brands, rather than looking at the market value of the particular product or brand.

Tips on how to price your products

- When establishing prices for new products, giving consumers several pricing scenarios in the research stage can help determine what they are willing to pay

- Competing simply on price can be detrimental to long-term stability and continual discounting can devalue a brand

- Delivering targeted advertising can help raise the value of a brand in consumers’ eyes

- Having a democratic approach to pricing that involves both marketing and commercial teams is likely to deliver the best results

- Pricing policies should be reviewed on a regular basis to keep prices competitive and in line with outgoing costs

References

- ^ see below (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ see Q&A below (www.marketingweek.co.uk)