Comeback brands: Raising the dead

Golden Wonder, Kestrel lager and Polaroid are all staging comebacks - a risky plan considering the hostile economy and the fact consumers have long since moved on. Are they doomed to die again?

Wispa’s done one, BBC 6 Music avoided one and Golden Wonder hopes to achieve one: I’m talking about the comeback. Losing the love of consumers, being at the mercy of a brand owner looking for cuts or being usurped by a competitor is something all brands face but some of those that people thought consigned to history are now staging the risky but potentially rewarding resurrection strategy.

As the bleak economic climate shows little sign of improving, companies, including Golden Wonder, Kestrel Lager and Polaroid, are asking themselves whether it is possible or worth reviving dying brands.

The death of a once-great brand is often a cause for shock and sadness among consumers. Even if the business model has become obsolete, people retain an emotional attachment to the brand based on years of heritage and goodwill.

But goodwill alone does not bring success. Brands considering a comeback face issues such as how to find relevance when the market has moved on, how to convince retailers to stock your product and how to get the overall business model right.

Golden Wonder group marketing director Scott Guthrie is confident in his brand’s comeback. Founded over 60 years ago, Golden Wonder was once the biggest selling crisp brand in Britain but it was overtaken in the 1990s by Walkers which outspent and outsmarted it.

Golden Wonder’s decline was exacerbated by poor management, and in 2006 the business went into administration, resulting in a takeover by Northern Irish snack company Tayto. Today, Golden Wonder’s share is less than 2 per cent of the UK crisp market.

Guthrie concedes that the brand cannot hope to regain its market-leading status but he believes Golden Wonder can grow as a vibrant challenger brand. His focus for now is on reminding consumers of the brand’s existence and what it stands for (see Q&A).[1]

“There’s a misconception that Golden Wonder is a brand that died,” he notes. “There’s a difference between brands that have died and those that have been outplayed. Inherently there’s nothing wrong with the brand - it got passed from owner to owner for a number of years and now has a home where it can be nurtured.”

Since taking over, Tayto has focused on rebuilding Golden Wonder’s retail distribution and on developing new flavours, such as through a partnership with Heinz. Its efforts have reaped impressive results: sales of Golden Wonder increased by 47 per cent last year, according to Nielsen. Having stabilised the brand, Tayto is now looking to market Golden Wonder more vigorously and remind people about what they once loved about the brand.

Last month, for example, it launched a social media campaign calling for cheese & onion crisps to be sold in green packets and salt & vinegar in blue[2] - a clear challenge to Walkers, which has the opposite colour system. Guthrie, who joined Tayto last November, says the campaign is intended to spark people’s memories and encourage them to re-engage with the brand.

Fond memories

Achieving the right balance between evoking the past and looking forward is vital in any comeback. Last month, Sony combined the two in its TV ad for the new Xperia Z smartphone, in an attempt to stem the downward trend in its finances, having posted a ¥50.9bn (£353m) loss in February, adding to huge cumulative losses over the past four years. The expensively produced TV spot shows a series of iconic Sony products such as the Walkman, Camcorder and PlayStation before ending with the Xperia Z and its new waterproof technology.

Sony Mobile marketing director for the UK, Ireland and Netherlands Catherine Cherry explains that the campaign is intended to remind people about their affection for Sony while boosting its standing in the smartphone market. “Our research shows that pretty much all consumers have had a positive brand experience with Sony before,” she says.

“The challenge is Sony has relatively low brand awareness as a smartphone manufacturer. With this campaign we’ve tried to remind consumers about all the good experiences they’ve had with Sony and show them how we’ve worked that into the Xperia Z.”

Colour scheme

Similarly, Golden Wonder is hoping to build on people’s positive experiences of the brand and is focusing on colour as a strong memory jolt. Guthrie says: “The good news is the brand has huge residual awareness - there’s still a lot of love for it out there. When I was approached to join the business, the first thing I did was look at what people talk about when it comes to crisps. Colour, for a certain generation, is a very emotive subject so we decided to tap into that.”

Meanwhile, Sony’s look back at its glory years is understandable in the context of its recent financial troubles. Analysts have blamed Sony’s woes on its decline in the consumer electronics market, where companies such as Apple and Samsung have stolen a march, and on the fact that the brand is spread over a broad range of products as well as media production operations.

Sony draws on its range of products such as the HD screen and media content for smartphone Xperia Z

The new Xperia Z campaign, as well as the phone itself, are intended to focus the brand around a new flagship product. Using the tagline ‘The Best of Sony in a Smartphone’, the device incorporates different aspects of Sony technology such as a HD screen adapted from its Bravia televisions, through to access to content from Sony’s music, film and gaming divisions.

Cherry says Sony is focusing on the brand experience rather than just the product. “For us it’s not just about the hardware,” she adds. “Sony is the owner of a smartphone company that also owns a picture studio and Sony Music. That means we’re uniquely positioned to bring all of that content into the smartphone.”

Spotting an opportune gap in the market is what Golden Wonder is doing too. A recent backlash from vegetarians against Walkers crisps gave Golden Wonder an opportunity to deflect some of that interest on to itself. Walkers had decided to add meat to its smoky bacon and roast chicken flavour crisps for the first time, causing outrage among vegetarians. Golden Wonder quickly updated its Facebook page with banners displaying tongue-in-cheek slogans such as ‘vegetarians welcome’ and ‘no animals were harmed in the making of these crisps’.

“As a challenger brand we have to be able to jump on opportunities when they present themselves,” Guthrie explains. “There’ll be a lot of disenfranchised consumers out there who’ll now be looking for an alternative so we had a great opportunity. We saw a huge uplift in interest in the brand as a result of that activity.”

Culture change

Forbes columnist Bill Frezza believes that a company’s corporate culture is vital to the fortunes of its brand. He cites Apple as a classic example of a comeback brand, noting that Steve Jobs played a crucial role in turning around its fortunes after he returned to the business in 1997.

“Apple was heading for death, its culture was dying and it was revived by Steve Jobs,” says Frezza, a fellow of the Competitive Enterprise Institute in the US.

“Apple is so much an expression of Jobs’ personality that I believe Apple is now at risk in the long-term. If it’s well managed it will last a long time and earn returns for stockholders, but to continue to think of Apple as a growth company with Jobs gone would be wrong.”

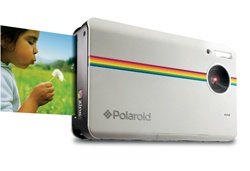

Frezza draws parallels with Polaroid, another iconic American brand that was driven by the passion of its founder, Edwin Land. The inventor turned Polaroid into one of the world’s biggest companies by developing polarisation and instant camera technology. But in the late 1970s, Land’s attempt to develop an instant movie system called Polavision resulted in financial disaster.

“[Land] was a reckless gambler who gambled his company on every product launch and won every time until the last one,” claims Frezza. “The company went down and never came back and the brand lost its value because it was so closely associated with Land.”

Today, Polaroid is being rebuilt under a completely different business model. After going into administration in 2008, Polaroid was acquired by a group of private equity firms who turned the business into an intellectual property holding company focused on brand marketing and licensing. In other words, Polaroid as a company no longer makes anything but rather licenses its name to partners around the world to produce branded products and services.

Polaroid president and chief executive Scott Hardy believes this model is “blazing a trail” for all types of consumer electronics businesses (see Viewpoint)[3]. “We view our role as curators of innovation,” he says. “We set the style guide, design direction and marketing strategy but we let third parties who are experts in manufacturing and distribution make it happen and take it to market.”

New vision

This ‘curation’ role means the Polaroid brand is attached to a broad range of products, including a line of eyewear and sunglasses first developed in the 1950s and digital products such as WiFi camcorders and children’s computer tablets. Earlier this year, technology start-up Socialmatic announced a deal to use the Polaroid name on a new digital instant camera that enables users to add Instagram filters before printing their picture.

Hardy says Polaroid’s 75-year history in visual technology has allowed the brand to stretch into areas beyond pure photography. “Because Polaroid is a visual brand, we’re finding it has an ability to move into any category that’s visually oriented,” he says.

As a curator of innovation, Polaroid ‘infuses’ its well-known brand attributes, such as the rainbow into new products

“A lot of that is down to our history. When Polaroid was founded in 1937 it produced the polarised technology that was used in goggles worn by Second World War fighter pilots. So it’s a brand that can move into categories outside of instant photography.”

Hardy claims that by maximising the brand in this way, Polaroid is growing impressively and delivering strong returns for investors but figures are not given out by the company. Last year, the brand expanded its distribution in the UK through a deal with Asda which grants the supermarket chain exclusive rights to sell Polaroid flatscreen televisions. Last month in Florida, meanwhile, Polaroid launched the first of 10 planned experiential retail stores that aim to encourage people to print out digital images from their mobiles and social media pages.

“We’re a brand that’s going through a tremendous resurgence right now,” says Hardy. “I don’t know how long it’s been since Polaroid has been so profitable and able to distribute dividends to our shareholders at the level we’re doing now. We have a business model that wins every time and is thriving.”

Flying high again

Elsewhere, Nigel McNally, managing director of Brookfield Drinks, agrees that a new business model can help to save a brand. He set up Brookfield in September 2012 after buying the lager brand Kestrel from Wells & Young’s, the drinks group where he previously worked as marketing director (see Case Study)[4].

Last week, Brookfield relaunched Kestrel in new packaging and with a stronger focus on its Scottish heritage and specialist brewing method. In the coming months the company plans to roll out other variants of Kestrel, including the 9 per cent ABV (alcohol by volume) ‘super strength’ variant for which it is famous. However, for now, the lager will only be available in independent shops, although Brookfield is keen to get it back into supermarkets.

McNally, a drinks industry veteran who has worked on brands including Corona, Bombardier and Red Stripe, says his aim is to focus attention on neglected but still valuable brands. “Our model is to put together a number of drink products that have been neglected by the brand owners - usually through no fault of those owners,” he explains.

“If you look at the portfolios of most larger drinks companies they tend to be quite extensive and the fact is you cannot give each brand the same level of tender loving care. You have to prioritise.”

In addition to using PR and social media for last week’s launch, McNally is working on a marketing strategy for Kestrel which he says could include TV advertising. He is also in talks about acquiring two more brands, with Brookfield aiming to become a home for all drink types, not just alcohol.

McNally suggests that while reviving a brand requires specialist expertise, success and growth are possible where the brand still has value with consumers. “You need to have a good understanding of the essence of the brand, how to unlock that and how to make it relevant to the consumer,” he says.

“With neglected brands you often find that if you spend a bit of time and attention on them, you can achieve some wonderful things.”

For Golden Wonder, this means more than performing PR stunts, such as its ‘vegetarians welcome’ Facebook activity. Tayto is keen to move the brand forward and make it relevant to a wide range of consumers once more. Guthrie reveals that this will be the focus of an advertising campaign planned for this summer.

“We need to give people a reason to choose us when faced with a choice of crisp brands,” he says. “They need to know what they’re going to get from a Golden Wonder product that they can’t get from another brand. That’s not going to be about nostalgia because that’s not a long-term strategy.”

The buried brands

Aqua Libra

Orchid Drinks dropped Aqua Libra in the ’80s but there was an outcry from fans and Britvic bought it but quietly axed the brand in 2009.

Huggies

Kimberly Clark pulled the nappies brand last October because of ‘negligible’ profit. Other products in the range remain, however - its Pull Ups are used by one in three mothers.

Flora White

Unilever axed cooking fat Flora White in 2011, likely because it didn’t sit well in the range, which is focused on healthy eating.

The born again brands

Wagon Wheels

The biscuit never really went away but has been relaunched twice recently. A French & Saunders sketch sparked a boost in 2002 and last year Burton’s Biscuits relaunched them again using the line ‘The truth is in there’.

Jessops

The bankrupt business is back. In the last week new owner Dragons’ Den star Peter Jones has opened six shops in a joint venture with Hilco. There are plans for 30 more.

Old Spice

The aftershave brand is no longer the butt of the joke. Procter & Gamble relaunched it at the 2010 Super Bowl and claims body wash sales rose 40 per cent in the first three months since.

References

- ^ (see Q&A). (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ calling for cheese & onion crisps to be sold in green packets and salt & vinegar in blue (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ (see Viewpoint) (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ (see Case Study) (www.marketingweek.co.uk)