Blending into the crowd

Never say being average means being irrelevant: new research finds it could be the key to long-term brand success because consumers prefer ‘normality’ - and there are major brands proving that the theory matches the reality.

Above: Heinz founder Henry J Heinz said: ’to do a common thing uncommonly well brings success’

No brand strives to be average. Average is run of the mill and can be associated with mediocracy, boredom and normality. But being average could actually be the secret to long-term success, according to new research shown exclusively to Marketing Week.

A study by Sign Salad carried out on GMI’s online panel reveals that 75 per cent of people agree that mid-market products are better because they can be trusted to deliver, while 78 per cent believe mid-level brands are ‘reliable and perfectly good enough’.

Positioning a brand in the middle of a category may sound counterintuitive, but brands that fit in rather than stand out are more noticed because things that are average have a deeper psychological resonance than things that are special, according to Michael Bloomfield, senior semiotician at Sign Salad (see Koinophilia box).

“A stand-out, atypical product might be more likely to grab people’s attention, but an average brand would be playing the long game,” he says. “Brands like Heinz, Kellogg’s and Nescafe are not interested in gambling on fads to grab your attention. As a result, consumers have more faith in them as they are extremely reliable. That is precisely why they are still around. They have become woven into our cultural fabric.”

Marketers should be looking to ‘semiotically identify’ the most repeated signs and symbols in any given category, he says, because these are the triggers that will be most familiar to consumers and therefore encourage trust and comfort in the brand.

“Obviously, if you describe yourself as average that will create a sense of stigma,” warns Bloomfield. “But if you create a product or brand that is middle-of-the-road, without describing it as such, you will bypass consumers’ sense of disgust and tap into something that resonates very deeply in us all. There’s no unconscious stigma.”

Gayle Harrison, brand director at Heineken UK, which owns Foster’s, says: “If you’re a big mainstream brand, it follows that you want to appeal to a big mainstream audience, so it’s important that the core brand is based on something that has that ability.”

The strength of the core Foster’s brand with its clear mass-market positioning gives the ability to experiment and push its boundaries

But while mass appeal is vital for any mid-market brand, she says it’s also crucial to have a distinct brand positioning in order to stand apart from the competition. “People know exactly what the Foster’s brand stands for and it’s very different to a brand like Carling or Carlsberg,” she claims. “You still need to be distinctive but without being polarising.”

The research also reveals that 63 per cent of respondents consider new product variations as branding gimmicks, prefering instead to stick with the original, while 86 per cent like no-nonsense brands.

“Branding people may be alarmed to hear [that] many of their innovative products might really be seen as gimmicky,” says Bloomfield. “At least one aspect of people’s psychology likes the ‘Ronseal factor’ [a product that ’does what it says on the tin’].”

But there are exceptions to the rule, which Vauxhall’s head of brand Martin Lay is keen to point out.

“A lot of car manufacturers have had to expand into different segments to capitalise on changing consumer needs, which has meant a real growth in our range,” he says.

Vauxhall has launched five new models since May last year: the electric Ampera, premium multi-person vehicle Zafira Tourer, small SUV Mokka, customisable city car Adam and convertible Cascada.

“None of these replaced an existing car in our range: they are all additional models. Within the car market, it is essential to cater for the different needs people have. It keeps the brand fresh. I completely accept that we benefit and thrive from the fact that we are an established, trustworthy brand that people know, but consumers won’t just blindly follow us if we come up with something too extreme.

Innovation is important because it helps broaden the brand footprint but for it to work, you have to focus on your core brand

”This year we are really pushing the fact we are 110 years old, but the reason we have survived for 110 years is by innovating and making sure we are meeting people’s needs.”

It is this heritage and brand trust that almost gives ‘average’ brands license to innovate, according to Alex Gordon, chief executive of Sign Salad, who singles out lager brand Carling as another example of where product innovation can work, after it launched a cider brand earlier this year.

“It has got ’permission’ to release these new variants, which are stand out, precisely because its core variant has been so unchanging,” he says. “Carling is ’koinophilic’, or average, because it is the most British beer of British beers. But brands like Carling only have license to create avant garde variants and push boundaries at the borders, if its core brand satisfies that averageness and reliability.”

Foster’s Harrison adds that there is generally less innovation in the beer category, so when new products are launched they tend to be longer standing.

In the past two years, the beer brand has brought two line extensions to market. Foster’s Gold is positioned as a premium bottled lager, while Foster’s Radler combines beer with lemon juice and is lower in alcohol.

“We’re not massively proliferating, but we’re building on very clear consumer insights. We have developed a proposition for a specific consumer type or occasion that wasn’t being met by our main brand. The key is to make sure you’re meeting a different need through innovation. If you’re just doing the same thing in a different way, then maybe consumers will find that gimmicky.”

In the first six months since the launch of Foster’s Radler it sold 13 million bottles. To put that into context, Foster’s sells 3 million pints each day in the UK, but it is helping the brand reach new customers who may have different objectives to their core drinker (see Q&A).[1]

“Innovation is really important because it keeps us vibrant and helps broaden the brand’s footprint, but in order for innovations to work you have to focus on your core brand. That’s the real source of volume, certainly in our case, and that’s where all our brand meaning comes from, so you have to continue to focus on the master brand even if you do innovate,” she adds.

Vauxhall has launched five new models since 2012

This constant innovation is the very reason brands like Heinz - which could be classed as average and is certainly mass-market - have survived for as long as they have, according to Giles Jepson, vice-president of marketing at Heinz Europe and chief marketing officer at Heinz UK & Ireland.

“Founded more than 140 years ago, Heinz products are as relevant today as when they were first sold in London’s Fortnum & Mason and have become part of the national diet, offering family mealtime favourites,” he says.

“Heinz’s relevance is also derived from its consumer-driven innovation such as Heinz Beanz Snap Pots and Fridge Pack, as well as driving emotional engagement with campaigns such as ‘Get Well’ Soup.”

In fact, the brand’s founder Henry J Heinz said himself “to do a common thing uncommonly well brings success”.

It is easy to forget in today’s market that when Kellogg’s first launched cornflakes more than 100 years ago it was highly innovative as no-one had boxed and sold a cereal like it before. But over time it has turned into a typical cereal brand, says Bloomfield, adding “there’s no reason you can’t innovate what turns out to be an average or typical product”.

The pulling power of average brands becomes even more apparent during times of economic difficulty, the research finds, because time and money become even more important to consumers.

“One of the most powerful things about an average brand is that you just don’t have to think about it,” says Bloomfield. “Consumers don’t want to have to analyse whether a particularly cheap product is good value or if a premium product is worth the extra money.”

When buying food from supermarkets, more than half (54 per cent) of those surveyed believe that there is too much choice, which is another reason why middle-of-the-road products could seem appealing as consumers do not have to wade through the various options, they can just go with what they know is reliable.

“Brands obviously want to offer as much choice as possible and people tend to think choice is a good thing, but the problem with choice is that it takes time and energy. Average brands can really help consumers make choices much more quickly,” says Bloomfield.

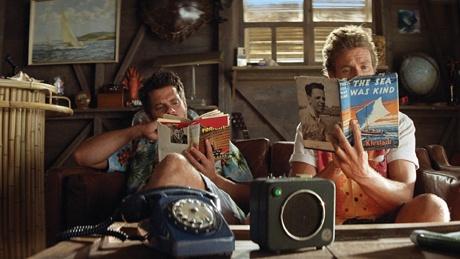

Foster’s TV ads assert that being average doesn’t mean being bland - it still has a distinct personality

Jepson from Heinz agrees that squeezed budgets have had an affect on the way people shop.

“Heinz has found shoppers are more price savvy than before due to the current economic climate. Their disposable income is tight and confidence is low. Heinz continues to offer value for money without compromising on quality while meeting different consumer needs through convenience, pack formats and sizes.”

Very few people actively go looking for new products either, according to the research, with just 6 per cent believing it is crucial to their shopping experience. Instead speed (18 per cent) and cost (45 per cent) are the most relevant.

However, while cost is high on the agenda, it’s also worth noting that the majority of consumers (55 per cent) opt for supermarkets’ standard products, and not the value range (22 per cent) or the premium alternative (20 per cent).

At Sainsbury’s, 95 per cent of customers have bought from the By Sainsbury’s range over the past 12 weeks, according to head of product brand Kirstin Knight. Meanwhile, 58 per cent have bought its Taste the Difference premium own-label goods, 71 per cent its Basics products and 80 per cent of baskets had all three ranges.

“This is because customers manage their budget by treating themselves in some areas on our more premium products, and therefore saving money in others to make their total basket balance versus their budget. Having said that, By Sainsbury’s [the standard own-brand goods line] makes up over two-thirds of our total own brand sales, so the bulk of products are bought through the core brand,” she says.

As Gordon suggested previously, the fact that Sainsbury’s built the foundations of its business at the mid-market level meant it was able to gain consumers’ trust before successfully expanding its offering to include luxury and basic ranges.

Knight says: “By Sainsbury’s is the heart of our own brand offer, with our other brands acting as supporting/complementary brands. It makes up almost 40 per cent of our business sales and we see it very much as the core evidence of how we help our customers ‘Live Well For Less’.”

She adds: “As such, it was important to establish this first, and to continue focus on this for our customers.”

There are examples of premium brands looking to enter the mid-market in order to cash in on the masses such as Jaguar and Apple, but to do so successfully they too will have to ensure they do not lose sight of their core product, devalue the brand and risk alienating existing customers.

It is difficult to believe any progressive brand would set out to be average, despite the results of the survey, and even less likely that they would actively market themselves in this way, but Gordon insists that it is the language of the word average that is pejorative, not the visual signs of it.

“If you use the word average, it loads up a lot of other cultural baggage that suggests something is ordinary and unimaginative. They are negative words. The brands we’re looking at don’t use that language at all, they use signifiers of typicality in each of their categories, which is appealing and desirable to consumers.”

Heritage brands

Average brands are often heritage brands as they have a long-standing relationship with consumers and have built up trust and reliability over a number of years.

Car marque Vauxhall puts great emphasis on conveying its 110-year history, and the fact it is one of the longest running UK manufacturers. Martin Lay, head of Vauxhall brand, says: “We’re trying to capitalise on the desire in people for all things British, particularly post-2012 with our success in the Olympics and the focus on the Queen’s Jubilee. We’ve been closely monitoring it to see when the time would be right to make more of our Britishness, and for a few years it wasn’t something we could really capitalise on, but we really think there is a need in people now to be buying British so that is something we’re really pushing.

“It’s not just about being known and trusted, it’s about being known, trusted and British.

References

- ^ (see Q&A). (www.marketingweek.co.uk)