A reputation in tatters

The horsemeat scandal, criticisms of fizzy drinks and a report slamming FMCG supply chains have rocked the food industry. Trust is at an all-time low, so how can the sector regain consumers’ favour?

The food industry is suffering its worst crisis since the BSE scandal in 1996. In the past few weeks, retailers, manufacturers and restaurant brands have found horsemeat in their beef products, the fizzy drinks industry has been rapped by medical groups for helping to cause obesity, and Oxfam has criticised the ethics of FMCG companies’ supply chains in its Behind the Brands report.

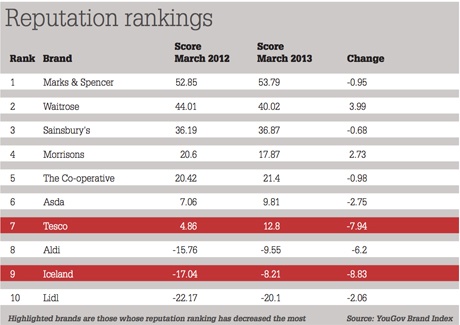

Although the food and drink sector is generally one of the most trusted - coming third after technology brands and the automotive industry in this year’s Edelman’s Trust Barometer - it will now become an uphill struggle to retain this trust and it is marketers who will be called on to help protect a brand’s reputation. Nearly 40 per cent of shoppers are less trustful of their main supermarket in the light of the ongoing horsemeat scandal, according to Canadean Custom Solutions, which spoke to 2,000 consumers last month. Added to this, more than half are sceptical about the quality of their supermarket’s meat. However, 88 per cent are more likely to blame suppliers for the contaminated meat.

The management of supply chains has been highlighted but whether marketers can have an effect on this operational side of the business is questionable.

A former Tesco marketer says the department should have a clear understanding of the supply chain. “A retail marketer’s role is to get the product on the shelf and support the sale, including the packing and positioning of the product in-store, the point of sale material, the shelf-edge label and making sure the product is at the right price.

“Understanding the supply chain along with the quality has always been down to the buyer. As a marketer, if I was working in the retail spectrum today, understanding the supply chain would be on my to do list now more than ever and would provide me with a greater insight to position the product correctly.”

Tesco, the first retailer to be embroiled in the scandal, has sent letters to its customers, and chief executive Philip Clarke spoke at the National Farmers Union conference in February. It has also run national press advertising and set up Tescofoodnews.com to address consumers’ fears.

Clarke states: “I know that the discovery of horsemeat in products sold in several major retailers, including Tesco, has shaken your trust in food retailers and the products we sell.

“You’ve told us that you want to buy British. And that the journey from farm to fork should be far less complicated. I’ve listened to what you have said and we’re making some real and lasting changes.”

And just last week Asda withdrew two of its frozen pizzas from sale, in line with its statement that it wants customers to have confidence in its food. At Asda’s results presentation last month, chief executive Andy Clarke said of the scandal: “It may have happened in the supply chain, but for our customers that is not their problem, it is ours, and we have to fix that.”

While all of the big four supermarkets and others are clearly responding to the crisis, none returned requests for comment.

Debbie Keeble of premium product Debbie & Andrew’s Sausages, which launched brand Heck with creative agency Elmwood last December, agrees that everyone should take responsibility for themselves. She calls for more transparency on where meat is sourced in the first place.

Keeble says: “There needs to be more controls in place and not just to suit an auditor - controls that really matter. That should come from the manufacturers if they are making it for the retailers but the retailers also need to check them out for themselves. You can’t say: ‘Well they told me it was OK and I believed them,’ that’s not good enough.”

This desire for trusted information increases during a food crisis. Lloyd Burdett, head of global clients and strategy at The Futures Company, part of research company Kantar, says the UK consumer looks to the retailer as a trusted authority.

He says this time the retailers have been “found wanting, not entirely because of their own fault but equally they have a share of the blame”. He adds: “There is another story coming out every couple of days. Consumers are fed up of hearing it and won’t trust any kind of processed beef product unless it’s clean and is declared as clean by the government.” (See Trust in food brands - the stats, below)

A spreading distrust

It is not only the beef industry that is suffering; the reputations of fast food and fizzy drinks brands are also on the line. A report last month called for a ban on advertising junk food on TV pre-watershed, and for a 20 per cent tax on fizzy drinks prices. An Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AoMRC) study has directly drawn the marketing and advertising industry into the debate.

“There is the bottom-line argument that the industry spends over £1bn a year in the UK on advertising processed foods and sugary drinks,” says Simon Capewell, professor of public health at the University of Liverpool and member of the UK Faculty of Public Health, part of the AoMRC. “We are all fairly sophisticated adults about this: we know it has an effect. Clearly folk in the advertising industry will argue that it’s a small effect and they are being picked on.

SodaStream is pursuing a strategy of honesty about its ingredients

“What we are tapping into is a progressive shift in public opinion. There is an increased awareness of what we are actually eating and on what represents healthy and less healthy options. That doesn’t mean putting soft drink companies out of business tomorrow, it just means a rebalancing.”

The report aims to start making some changes in the fight against obesity in the UK and looks to protect children. It is an issue that Fiona Hope, managing director at fizzy drinks brand SodaStream, believes is on a worrying trajectory.

Hope suggests that from a brand perspective, a government education initiative can be supported with “honest and true marketing strategies” to allow consumers to make informed purchasing decisions based on ingredients and their preferred diet.

“Greater investment is required to educate the public on the importance of a well-balanced diet, as well as moderate consumption of convenience foods and high sugar drinks,” says Hope. “Honesty around ingredients, sugar and fat content is also something that is imperative for brands to adhere to if we are to improve the childhood obesity rate in this country.” (See Viewpoint.[1])

Community effort

The Department of Health, which launched the Change4Life campaign to tackle obesity in 2009, announced that from April, local authorities will be given a ring-fenced budget of £5.4bn over two years to help tackle public health issues such as obesity in their communities.

However, health minister Dr Dan Poulter says it is brands and marketers that must respond: “This is not just a matter for government, we look to industry, health professionals and voluntary groups to work jointly to help individuals improve their diet and lifestyles.”

Oxfam’s Behind the Brands report, published last month, slams food companies for poor ethical standards and encourages consumers to quiz them via social media.

Consumers want more information on where ingredients come from

Oxfam spent a year investigating the policies of the world’s top 10 food and drink companies that claim to be acting ethically in the supply chain.

The report looks at seven criteria and ranks each company according to how well it does in areas including the transparency of supply chains and operations, how it ensures the rights of workers and farmers who grow ingredients, the protection of women’s rights, the management of water and land use, and policies to reduce the effects of climate change.

Associated British Foods (ABF), owner of brands including Silverspoon, Amoy and Kingsmill, is labelled as the worst of the ‘Big 10’ global food and drinks companies, although none of them scored a good rating overall.

“The idea of this ranking is to give customers the opportunity to use social media to put pressure on the companies to do the right thing and show that consumer pressure does reward them in their building of trust,” says Oxfam director of campaigns Phil Bloomer.

ABF strongly denies the accusations, stating: “We treat local producers, communities and the environment with the utmost respect.”

John Steel, chief executive at Fairtrade hot drinks company Cafédirect, believes that Oxfam is in a credible position to highlight the “huge gap between rhetoric and reality”.

“Ultimately, the Oxfam report is a building block and hopefully the start of a bible of background information that cuts through the gloss.

“Consumers need an independent source of information about the brands and companies that they are investing in through their custom and in turn brands need to know they will be exposed if they don’t live up to their promises.”

Accountability

Steel argues that having and proving accountability is where supermarkets in particular can regain trust from consumers.

“Retailers do have a clear role to play. It was refreshing to hear the response from the Co-operative Group chief executive Peter Marks, who accepted ‘ultimate accountability’ for the products that it sells.”

Consumers put particular emphasis on the provenance of red meat, with 20 per cent saying that where it comes from is very important, according to a YouGov Sixth Sense report[2], produced in asociation with Marketing Week. By contrast, 14 per cent say the provenance of milk is key and 12 per cent say the same for cheese.

But supermarkets also have to remain in business and keep their shareholders happy, while making sure their products are up to scratch, says the former Tesco marketer, who wishes to remain anonymous. “Over time, the need to drive efficiencies and savings to increase margins will always be a goal for retailers in Britain, which have shareholders to keep happy, so one can only assume that as time goes by and shareholder demands increase, quality will be under the spotlight for consideration.”

The former marketer believes that if these kinds of situations are well-managed, consumer trust will be regained. “The best retailers are the ones that get on top of the situation straight away with a strong PR campaign, retaining their own customers and stealing some from the competition. The Tesco brand will remain intact as will other supermarkets which deal with this situation effectively.

“It is interesting to see the marketing plans that have been put in place by supermarkets but what comes into question is: how well do retailers know their suppliers?”

This is where the opportunity lies for businesses that are looking to regain consumer trust. Open and honest behaviour will help the industry regain the faith and it is marketers who are helping brands achieve this.

Trust in food brands: the stats

More than a third (36 per cent) of people in the UK say they are less likely to buy processed meat than they were before the horsemeat scandal, according to research by Kantar, which polled more than 6,000 people across the UK. A quarter of respondents say they do not buy processed meat and a third say it will not make any difference to what they buy.

Forty-seven per cent of men say it will make no difference to their purchases of processed meat, compared with just over a quarter of women at 26 per cent. Nearly a third of women say they have never bought processed meat compared to 18 per cent of men.

Sales of processed foods have risen by a third in the past five years and have increased by 15 per cent in the past year alone but in the four weeks ending 17 February, frozen burger sales were down by 43 per cent and frozen ready meals declined by 13 per cent.

Ninety-three per cent of UK consumers consider price as a factor when deciding what to put in their shopping baskets. This contrasts with only 73 per cent who take health into consideration, 32 per cent who think about whether something is Fairtrade and 22 per cent who consider organic food.

References

- ^ See Viewpoint. (www.marketingweek.co.uk)

- ^ according to a YouGov Sixth Sense report (research.yougov.co.uk)